Share This Article

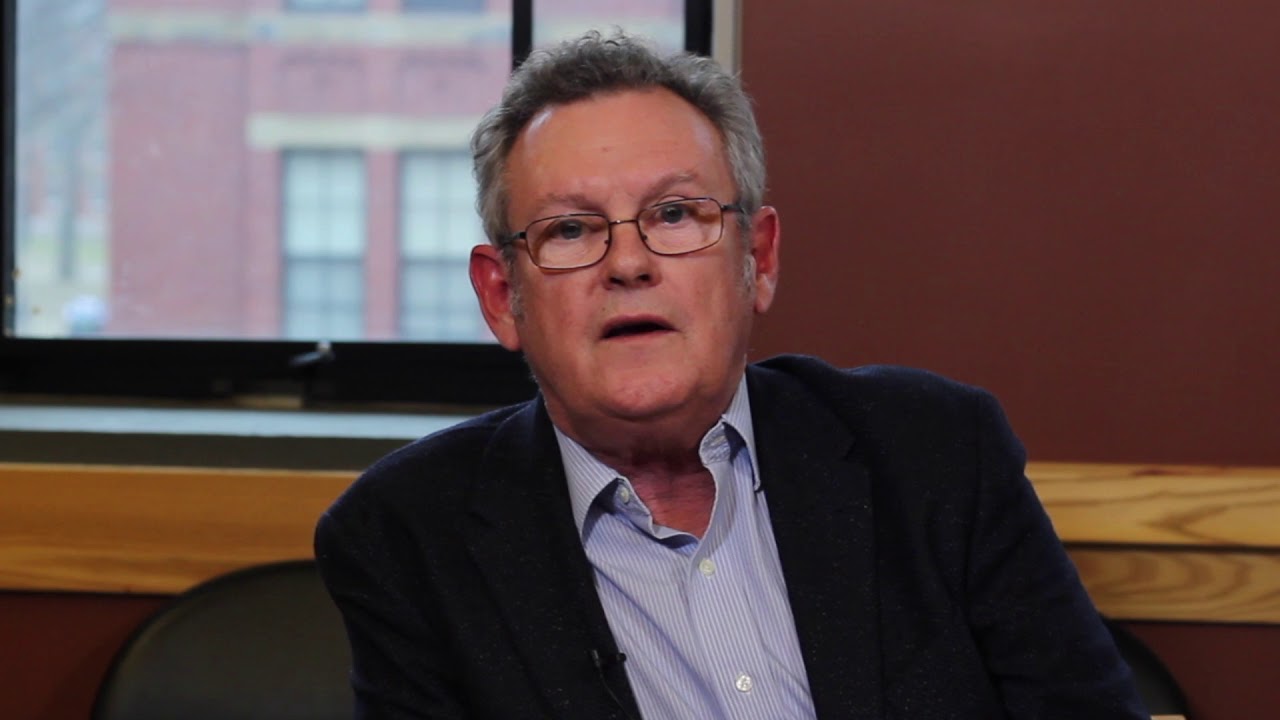

To celebrate Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday, Richard F. Thomas, George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University, discusses his essays about Bob Dylan. [Click here fo the Italian version]

Richard F. Thomas is George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University. He was born in London and brought up in New Zealand. He has been teaching a freshmen seminar on Bob Dylan since 2004 and writing essays about him for a number of years. One of his first contributions to the so-called “Dylanology” was his 2007 essay “The Streets of Rome: The Classical Dylan” (in Oral Tradition 22/1), where he tracked down references to Virgil, Ovid, Thucydides, and Italian literature within Dylan’s oeuvre. He is the author of Why Bob Dylan Matters (Dey Street Books 2017), one of the most timely and exhaustive collections of essays about Dylan’s work ever written, which has been finally translated into Italian by Elena Cantoni and Paolo Giovanazzi with the title Perché Bob Dylan (EDT 2021). To quote a passionate thought expressed by Italo Calvino, a classic is a work – not necessarily a book – that “has never finished saying what it has to say”, that “’I am rereading…’ and never ‘I am reading….’.”

Richard F. Thomas is George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University. He was born in London and brought up in New Zealand. He has been teaching a freshmen seminar on Bob Dylan since 2004 and writing essays about him for a number of years. One of his first contributions to the so-called “Dylanology” was his 2007 essay “The Streets of Rome: The Classical Dylan” (in Oral Tradition 22/1), where he tracked down references to Virgil, Ovid, Thucydides, and Italian literature within Dylan’s oeuvre. He is the author of Why Bob Dylan Matters (Dey Street Books 2017), one of the most timely and exhaustive collections of essays about Dylan’s work ever written, which has been finally translated into Italian by Elena Cantoni and Paolo Giovanazzi with the title Perché Bob Dylan (EDT 2021). To quote a passionate thought expressed by Italo Calvino, a classic is a work – not necessarily a book – that “has never finished saying what it has to say”, that “’I am rereading…’ and never ‘I am reading….’.”

As a result, we can certainly agree that Bob Dylan is an artist of the same caliber as the ones usually studied in traditional academic courses. His influence on musicians, poets and novelists is impossible to be summarized. We are always relistening and reliving his music while pondering on each single line, word or accent. His voice is a path for the Muses who are singing through him, as he said while finishing his brilliant Nobel Prize Lecture released in 2017. In the same Lecture, Dylan talked about some of the books which had inspired him the most, one being Homer’s Odyssey, the most ancient poem of Greek Literature along with the Iliad. It was not a surprise. Dylan started quoting the Odyssey in songs from his 2012 Tempest. Moreover, in concert, from 2014 onwards, he re-wrote “Workingman’s Blues #2” (from Modern Times, 2006) in an extended way, making it his “personal” Iliad and Odyssey, and perhaps also his Aeneid. He also changed some of the lyrics for “Long and Wasted Years” (from Tempest, 2012), adding a powerful quotation from Homer. Interviewed in 2016 by the Daily Telegraph, some weeks after being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Dylan said that some of his songs “definitely are Homeric in value”.

Although in Chronicles Vol. 1 (Simon & Schuster 2004) Bob Dylan gave details about his early approach to Thucydides and Machiavelli, Suetonius and Tacitus, and in his 1974 “Tangled Up in Blue” (from Blood on the Tracks, 1975) he sang about “an Italian poet from the 13th century”, specific references to Greek and Latin authors are somewhat recent within Dylan’s oeuvre. However, as Thomas points out in his book, Dylan’s fascination for Rome probably goes back to his trip to Rome in 1962, after which he wrote the unreleased “Going Back to Rome”. Rome comes up also in “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, released for the first time on Greatest Hits Vol. 2 (1971). Moreover, in his 2001 La Repubblica interview, held in Rome, Dylan talked about ages in Hesiodic terms, and in a 2015 interview for AARP Magazine he said that, if he had to do it all over again, he would have been a schoolteacher in Roman history or theology. Just when you think you have figured out his art, he has already moved forward, and he doesn’t look back. Today, he celebrates his 80th birthday.

Samuele Conficoni had the pleasure of talking with Professor Richard F. Thomas about why Bob Dylan “is part of that classical stream whose spring starts out in Greece and Rome and flows on down through the years, remaining relevant today, and incapable of being contained by time or place”, and why he “long ago joined the company of those ancient poets.”

Professor Thomas, what are the aims of your seminar about Bob Dylan, which you started back in 2004, and why did you choose this particular approach to studying and teaching Dylan’s oeuvre?

The aims have evolved, as Dylan’s art has continued to evolve. When I started teaching it we didn’t have Modern Times, Together Through Life, Tempest, Rough and Rowdy Ways. So my aim of introducing a group of 18-year-olds to the entirety of Dylan’s oeuvre has become increasingly unattainable. Some of the students come in knowing Dylan, a handful have known him very well. But my aim from the beginning was connected to a desire that the students really get into the dynamics of Dylan’s songs, how they work on the records and in performance from all perspectives, musical, literary, aesthetic, cultural, political. You could do an entire seminar on each of these aspects, so the seminar cannot be comprehensive, but we cover the great periods in particular, including the recent decades. A first-year seminar, with students preparing a limited number of songs and presenting their findings to the group, seemed the ideal way of having a community of young people add Dylan to the center of their canon, and that has worked over the years.

How would you present your crucial Why Bob Dylan Matters to Italian readers who will read it for the first time? I think it is one of the most essential books ever written about him.

I hope Italian readers will enjoy the book. Like Dylan, I was drawn to Rome and to ancient Italy as a boy, for me in New Zealand, about as far as you could get from Rome. Through the films of the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few years later than Dylan, but many of the same films, The Robe, Ben Hur, Spartacus, Cleopatra. I started Latin about the same time, partly because of those films, and haven’t looked back. It was my main ambition to have the book appear in Italian, because that’s where large parts of it too were born. In Italy there is a respect for song and poetry and poetic traditions, obviously with Dante, poet of l’una Italia at the center, but going back through him to Virgil and forward through him to Petrarch and everything that followed, all the way up to Bob Dylan. Dylan realizes all of this, as he said in the Rome interview in 2001. That is in my view one reason he did those two spectacular, unique performances at the Atlantico in Rome on November 6 and 7, 2013. I write about how he was bidding farewell to more than a dozen of the songs he sang those two nights there in Rome, as a gift offering to the city, singing some of them for the last time.

Rome and Italy are in Dylan’s blood, going back to his boyhood and the Roman experience of his teens, and now alive and vital in his late 70s, from the Rubicon to Key West in the imagination of his new songs. I was able to get to Italy three years ago, in the early April spring of 2018, after the book came out, where I saw him at the Parco della Musica in Rome, and in Virgil’s native town of Mantua, across the Mincio in Palabam Mantova, now the Grana Padano Arena. That was a magical experience, the songs of Bob Dylan in the home town of Virgil. During the day I made my usual pilgrimage to the medieval statue of Virgil at his desk, also from the 13th century, carved in the wall of the Palazzo del Podestà, to Mantegna’s stunning frescoes in the Camera degli Sposi, to Ovid and his Giants in the Palazzo Te, and to the fascist Virgil monuments in the Piazza Virgiliana. Then from Virgil by day to Dylan at night, his setlist including “Early Roman Kings” and so taking me back to the daytime activities. I hope a lot of that comes through in the book.

How do your essays fit within Dylanology, particularly in relation to other influential contributions such as those by Christopher Ricks and Greil Marcus?

I’d be honored to have my names next to those two. Marcus’ work on the deeply American traditions of Dylan’s music, from the late 1960s in Invisible Republic to the more recent work on the place of the blues, in music and well beyond, are among the most important contributions, and not just to an understanding of Dylan. Christopher Ricks in a way made it OK to work on Dylan as an academic topic. Bob Dylan’s Visions of Sin lays out the ways in which Dylan belongs in the center of the literary traditions of the last two or three centuries, particularly the 18th and 19th. His engagement with the holistic elements of Dylan’s song poetics in his analysis of the rhymes, prosody and meaning of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” is magnificent. My book is somewhat different in its emphasis on more deliberate forms of intertextuality, involving Dylan’s verbatim use of authors, mostly but not only from classical antiquity, and in the way that the songs inhabit and become part of those traditions, bring them into the land of the living through his art.

I was interested in the new and profound ways in which, especially in the songs of this century, Dylan’s songwriting engages in what he has called “transfiguration.” That is something he has always done with the traditions of folk, as he pretty much spelled out in the Nobel Lecture in June 2017. There he spoke of picking up and internalizing the vernacular, but the way he describes that process is notable: “You’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy.” Heard, saw, pals with. That early transfiguration through the intertextual process lead

s to a parallel outcome with the classical authors, but more. When he sings “No one could ever say that I took up arms against you”, the singer of “Workingman’s Blues #2” becomes the exiled Ovid, whose precise words Dylan gives to the singer. When the singer of “Early Roman Kings” quotes verbatim

the taunt of Odysseus triumphantly hurled at the blinded Polyphemus from a specific translation of the Odyssey—“I’ll strip you of life, strip you of breath / Ship you down to the house of death”—that singer becomes Odysseus. But the singer was also “up on black mountain the day Detroit fell”, his 2500-year old transfigured singer also alive in the racial discord of the 20th century. So I suppose that tracing this role of intertextuality was one of the contributions of my book.

I have been studying Bob Dylan, the Classics, and Italian literature for many years. I have always found it wonderful to see how skilled and original Dylan is in connecting such disparate authors within his compositions. Nobody sings Dylan like Dylan, it is true, but I would go further and say that nobody writes like Dylan. How does Dylan “handle” his sources?

Yes, nobody writes like Dylan, as nobody in his art or anywhere in living creative practice reads or thinks like Dylan. Virgil, Dante and Milton did, and so did Eliot. Dylan has an eye for the poetry of language, as he encounters it in the eclectic reading and listening he does. Take the lines from verse 6 of “Ain’t Talkin’”, on the Modern Times album version, but not to be found in the official lyrics book: “All my loyal and my much-loved companions / They approve of me and share my code / I practice a faith that’s been long abandoned / Ain’t no altars on this long and lonesome road”. The first three lines come from three different poems in Peter Green’s translation of Ovid’s exile poems, as a number of us have recorded. Individual lines (Tristia 1.3.65, “loyal and much loved companions”; Black Sea Letters 3.2.38 “who approve, and share, your code”; Tristia 5.7.63–4 “I practice / terms long abandoned”) lifted from across 150 pages in the Penguin translation. And the altars on that long and lonesome road belong to the world of the blues pilgrim but also to Ovid’s world where roadside altars were a fixture from the Appian Way to the Black Sea. Nobody but Dylan could pick up that book and produce that sixth verse, completely at home in the song whose title started out its life in the chorus of a Stanley Brothers bluegrass song, “Highway of Regret”: “Ain’t talking, just walking / Down that highway of regret / Heart’s burning, still yearning / For the best girl this poor boy’s ever met.” And that is before we even start to trace the other intertexts: Poe, Twain, Henry Timrod, Genesis and the New Testament Gospels. Peter Green created poetic lines in his response to Ovid’s poem: “a place ringed by countless foes”, “May the gods grant … that I’m wrong in thinking you’ve forgotten me”; “every nook and corner had its tears”; “wife dearer to me than myself, you yourself can see”, and so on. Dylan took those lines and used them, just a few in each of the songs, and made them part of his own fabric—in one case even becoming a song title: “beyond here lies nothing”. As with the intertextuality in the hands of those other great artists, the lines he successfully steals and renews bring with them, once we recognize the source, their Ovidian setting, a poet in exile, in place or in the mind, getting on in years, “in the last outback at the world’s end.”

Also as with all great literature, Dylan is way ahead of the critics, or far behind his rightful time, which is to say the same thing. Early on there were even critics who denied the presence of Ovid in the song and on the album, partly because they just found any old Ovid translation online, and then the transfiguration doesn’t work. You have to work from the translation Dylan was using, the Penguin, as he used Robert Fagles’ Penguin of the Odyssey on Tempest. And a lot of people don’t like the idea that Dylan’s songs are composed out of the fabric of other materials, discrete as they are on this song. That is a throw-back to Romanticism, to Wordsworth’s notion that poetry is a “spontaneous overflow of emotion”, though that was never true, even for Wordsworth. I have no problem with intertextuality and transfiguration, because that is how my other poets worked, in antiquity and down through the Middle Ages and Renaissance to the end of the 18th century in the Latin and vernacular literary traditions.

Virgil’s incisive “debellare superbos”, “taming the proud”, from Aeneid VI, comes up in Dylan’s “Lonesome Day Blues”, from his 2001 masterpiece “Love and Theft”, and a fascinating allusion to the Civil Wars (whether they be Roman or American) appears on “Bye and Bye”, which is from the same album. On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan seems particularly fond of Caesar, who is directly mentioned in “My Own Version of You” and whose presence hovers around “Crossing the Rubicon”. What is Dylan trying to convey with those references?

Bob Dylan has been familiar with Julius Caesar at least since March 15, 1957 whether or not he remembers that spring day when the 15-year-old and the Latin Club of which he was a member published a paper commemorating those Ides of March up in Hibbing. By then his mind was more on the bookings his band The Golden Chords had at Van Feldt’s snack bar, but it is a historical fact, as I show, that he and the Roman dictator were acquainted early on. Shakespeare’s play could have helped the relationship since he had probably seen Marlon Brando playing Marc Antony in Joseph L. Manckiewicz’s 1953 movie version of the play. To be sure, that film, which returned to the State Theater in Hibbing on February 9, 1955, may well have been one of the reasons he enrolled in Latin the next fall. Who knows?

Dylan has always been interested in civil war, and was a historian of the American Civil War long before 2002 when he wrote and performed “’Cross the Green Mountain” for the 2003 film Gods and Generals. Around the same time in Chronicles, Volume 1, he talks about that seminal American conflict in ways that suggest he has long been inhabiting the middle of the 19th century in his mind, to the time when in his words “America was put on the cross, died, and was resurrected.” And the consequence of that inhabiting cannot be understated, as he continued “The godawful truth of that would be the all-embracing template behind everything that I would write.” Dylan quite perceptively sees in the southern plantation owners a mirror of the “Roman republic where an elite group of characters rule supposedly for the good of all” (Chronicles 84–85). Here he is again going back to Rome, as throughout his life.

By the time of Chronicles he had already conflated the American Civil War with its Roman versions, by combining Virgil’s Aeneid and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in “Lonesome Day Blues”, and yes, on the same 2001 album, by allusions in “Bye and Bye” (“I’ll establish my rule through civil war”) and maybe in “Honest with Me” (“I’m here to create the new imperial empire”). His interest continued in “Ain’t Talkin’” in 2006 where the connection to Rome is undeniable given how much Ovidian poetry there is on the song (“I’ll avenge my father’s death then I’ll step back”). Here he channels Caesar’s adoptive son, the first Roman emperor Augustus, who said in his own memoir “Those who killed my father I drove into exile, by way of the courts, exacting vengeance for their crime . . . I did not accept permanent the consulship that was offered to me.” He returned to this shared civil war and Caesarian theme—and to the hills of Rome perhaps—in 2012 in “Scarlet Town” (“In Scarlet Town you fight your father’s foes / Up on a hill a chilly wind blows”). I wrote about all of that in the book. And now there he is again in 2020, in “My Own Version of You”, a song that’s all about intertextuality, asking himself “what would Julius Caesar do”—and of course crossing the Rubicon, the signature act of Julius Caesar. Dylan is also interested in assassination of course, President McKinley in “Key West” and John Fitzgerald Kennedy in “Murder Most Foul”, so it’s not surprising that Dylan, who said if he had to do it over he would teach Roman history, has returned to Caesar. Of course, in “Crossing the Rubicon” it’s not just a theme, he’s become Julius Caesar, transfigured as he takes that fateful step at the end of each verse. As he so he fulfills the prophecy made in the Rolling Stone interview with Mikal Gilmore in 2012: “Who knows who’s been transfigured and who has not? Who knows? Maybe Aristotle? Maybe he was transfigured. I can’t say. Maybe Julius Caesar was transfigured.”

Alessandro Carrera, another relevant Dylan scholar and Professor at the University of Houston, has recently written about why Dylan often refers to Homer’s Odyssey from 2012 onwards. He thinks that Dylan’s metaphorical exile, represented by his references to Ovid’s later works (Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto) in Modern Times (2006), ended. He is now facing his nostos, he is “slow coming home”, as he sings in “Mother of Muses” (2020). In his opinion, the rewritten lyrics for “Workingman’s Blues #2” well represent his personal relationship with both Iliad and Odyssey. What is your view about that?

Yes, certainly the Odyssey, as I discussed when I wrote about those lyrics changes to “Workingman’s Blues #2”. I’m not sure how much Dylan has engaged the Iliad yet, though the Nobel Lecture brilliantly picks up on the Odyssey’s questioning of the heroic code of the Iliad, and of the shade of Achilles in the Underworld realizing that the quest for honor and glory was empty, that being alive was what mattered. Dylan has the Achilles tell “Odysseus it was all a mistake. ‘I just died, that’s all.’ There was no honor. No immortality.” That, by the way, is as brilliant a piece of intertextuality as you’ll find anywhere.

Yes, of course, nostos, and the return home. We’re all doing that, but home has shifted. Not Ithaca or Hibbing anymore, but a different home. That’s why Dylan includes Porter Wagoner’s great country song “Green Green Grass of Home” among the songs that had taken on the themes of the Odyssey. The singer imagines being back home, but in reality he’s in prison, about to walk at daybreak to the gallows with the sad old padre. They’ll all come to see him when he’s six feet under, under the old oak tree that he used to play on before his life went astray, maybe the same oak tree the singer of “Duquesne Whistle” remembers. You can’t actually come home. Dylan, like many poets going back to Homer, knows that. And that’s why, as I wrote in the book even before “Mother of Muses” came out, I suspected Dylan had been reading and channeling the great Greek poet of modern Alexandria. For Cavafy, the return to Ithaca is what is important, the living of life itself. The lines in his poem “Ithaca” tell that the island is just the destination, “Yet do not hurry the journey at all: / better that it lasts for many years / and you arrive an old man in the island.” That’s what comes to me at the end of Dylan’s “Mother of Muses”: as for Cavafy, so for Dylan and the rest of us, no reason to hurry that journey. “I’m travelin’ light and I’m slow coming home.”

What do you think of Bob Dylan as an historian? His way of reviving, rewriting and often changing the history is brilliant and meticulous. Does Dylan remind you of any Greek or Latin historiographers?

Of course, Bob Dylan isn’t a historian in the modern sense, in getting to some absolute factual truths. His early songs, perhaps reflecting some of the less imaginative teaching to which he may have been exposed, made that clear: “memorizing politics of ancient history / flung down by corpse evangelists” and “the pain / of your useless and pointless knowledge.” But it is interesting that he has in more recent years been mentioning ancient historians and thinkers, Thucydides, Cicero, Tacitus, since he shares with them outlooks about historiography of a more creative type. “History” contains “story”, and in Italian of course the word for history is precisely that, storia. Ancient historiography expected not so much truth—so often beyond reach—as believability, to be achieved, so said Cicero, by constructing the elements of the story, as with a building. Even the relatively factual Thucydides reports verbatim speeches he did not hear, along with those he did. The speeches he composes assume they would have been what was said, given the events that followed on the words. If those actions, then necessarily these words.

There is an element of storytelling here, putting together what must have happened. Likewise for Tacitus, whom Dylan mentions on various occasions, and who writes of Nero’s killing of his own mother, Agrippina: “The centurion was drawing his sword to kill her. She thrust out her stomach and said “Hit the belly!” and was finished off.” How did Tacitus know what she said? The matricide happened when he was about three years old. But it’s believable and it sounds good, and Tacitus, like Dylan, would have said you want your history to sound good. Take the historical ballad “Hurricane” about the murder trial of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. Did the cop really say of one of the victims, “Wait a minute, boys, this one’s not dead”? Probably not, but he could have, it’s believable, and more important it sounds good. In both cases the wording puts you right there at the scene.

So yes, songwriting has aspects of this old storytelling historiography. In a sense, folk songs, particularly ballads, are a form of oral history: “Robin Hood and the Butcher”, “The Earl of Errol” “Rob Roy”, “Dumbarton’s Drums”. Dylan’s versions are just updates, putting into story historical events of his own finding, sometimes from the obscurity of newspaper clippings or archives—“The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “Joey” about the deaths of two historical people. It doesn’t matter whether or not William Zanziger had a “diamond ring finger” or Joe really saw his assassins coming through the door “as he lifted up his fork”. Both are plausible, and both help paint a picture, or “finish off a building” (exaedificatio), the metaphor Cicero used for fleshing out the narrative.

“Ut pictura poësis” (“Poetry is like a painting”), Horace wrote in his Ars Poetica (Epistula ad Pisones). Back in 1974 Bob Dylan was deeply influenced by Norman Raeben, a New York artist who gave him painting lessons. Dylan himself is also a good painter. Do you think we could link Horace’s maxim to Dylan’s song composition?

As you know, Horace also goes on to elaborate the ways poetry, or let’s say songwriting, is like painting: some repays getting close up, some from standing back. He also distinguishes the poem/painting that you can look at/read just once, and the ones you can never get enough of, keep coming back to. Dylan’s songs are generally of that sort, you can keep coming back to them, never tire of them, especially as he changes the arrangement and performative dynamics from year to year and night to night. Dylan’s painting, and his sculpture, are very interesting. I need to see more of it and think more about it. I’ve had the experience of seeing the Mondo Scripto lyrics and drawings on a couple of occasions. I actually thought of Horace on getting up close during those experiences. There is something quite moving about being up close to the depiction of a scene from a particular song, juxtaposed with Dylan’s handwritten lyric. You’re reading, viewing, and also silently hearing the song in your head. This can produce an interesting synaesthesia, a productive mingling of the senses. As for Raeben, Dylan has of course spoken of him, and he and his teaching were clearly important for Dylan’s painting career. Critics talk of the impact on the songs of Blood on the Tracks, the visuality of lines from “Shelter from the Storm” and especially “Simple Twist of Fate”. Enargeia, the Greeks called it, vividness, and the ability to paint a picture in words. But that quality is already there in 1966 in “Visions of Johanna”. Who taught Dylan to write like that? The Muses, of course, as he finally came out and revealed on the new album.

In his significant 2001 Rome interview, Dylan deals with lots of topics, and one of the subjects which has always caught my attention, as you pointed out in your essays, was his reference to the “ages” of the world in Hesiodic terms. At some point the discussion fades out and another subject comes up. It seems that Dylan almost deflected the argument or was not in the mood for explaining his theory. What do you think Dylan means when he speaks about that? Does this theme come up in some of his songs?

Well, as you know, I write about that Rome interview in the book, though there is more to be said on that topic perhaps. Dylan actually mentions all of the five ages that appear in Hesiod’s Works and Days: the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age. Then “I think you have the Heroic Age someplace in there” and next “we’re living in what some people call the Iron Age.” That’s a pretty precise reference to Hesiod, the only ancient poet to have an age of Heroes along with the metallic ones. In Hesiod that’s probably a reference to the Homeric texts and the heroes who fight and die at Troy.

I don’t know why Dylan brought that up, but the journalists missed whatever point he was making. He finished with a non-classical reference maybe to deflect from those precise allusions: “We could really be living in the Stone Ages.” That gave the opening to a journalist who joked: “Living in the Silicon Age”, and so the moment was lost, the shooting star slipped away, as Dylan replied “Exactly”—in other words “you didn’t get it”—then “Silicon Valley.” I’ve often wondered what would have happened if one of the reporters had known what Dylan knew, and had asked “How do Hesiod and his metallic ages come into your songwriting?” Of course he could have deflected that too, as when one of them earlier in the press conference asked about new poets he was reading and got the reply “I don’t really study poetry.” So we’ll never know, but I do think he has been interested in the Greco-Roman ages, at least since the late 1970s. There are Tulsa drafts of “Changing of the Guards” that suggest he was reading Virgil’s messianic fourth eclogue, about turning the ages back and getting from the iron age present to the golden age utopian past. That’s where Jupiter and Apollo in the published version of the song come from, having survived the drafts.

In 2020 you published an essential journal article, “’And I Crossed the Rubicon’: Another Classical Dylan” (in Dylan Review 2.1, Summer 2020), which represents the natural continuation of Why Bob Dylan Matters. In this article you deal with “the classical world of the ancient Greeks and Romans in the songs of Rough and Rowdy Ways”. What “kind” of classical world did you find there?

Dylan himself points to what the album does with the ancients in the last interview he has done to date, with Douglas Brinkley in the New York Times of June 12, 2020. He did the same in advance of the release of “Love and Theft” at the Rome Press Conference in 2001, hinting at the presence of Virgil on that album: “when you walk around a town like this, you know that people were here before you and they were probably on a much higher, grander level than any of us are.” I don’t know why Brinkley in 2020 asked Dylan about “When I Paint My Masterpiece”: why did Dylan “bring it back to the forefront of recent concerts?” His response to that one was also a tell-tale sign, in this case about the album he released the next week: “I think this song has something to do with the classical world, something that’s out of reach. Someplace you’d like to be beyond your experience. Something that is so supreme and first rate that you could never come back down from the mountain. That you’ve achieved the unthinkable.”

The classical world on the new album, as I set out in the Dylan Review, is not so much a verbatim transfiguring of the ancient world, but a more freely creative version, “my own version of you.” So the cypress tree where the “Trojan women and children were sold into slavery” in the song, as I noted, comes from Book 2 of the Aeneid, but unlike the use of Ovid and the Odyssey, Dylan is not quoting from known translations, but doing his own version. I’ve gathered most of the material on the other songs, “Crossing the Rubicon”, “Mother of Muses”, “Key West”. So I won’t repeat that here. It’s a free online journal, though accepts contributions. On those songs you can see Dylan has scaled those mountains of the past he also sang about in “Beyond Here Lies Nothing”. My guess is part of him will stay up on the mountain, as I certainly have myself!

In the same article you wrote that the “intertextuality that has been a hallmark of Dylan’s song composition since the 1990s continues on the new album”…

Yes, I did, and it’s true. But it’s a freer version, more like that of Virgil or Ovid themselves, or Dante, Milton and Eliot, not quoting and juxtaposing—Virgil with Mark Twain and Junichi Saga in “Lonesome Day Blues” or Ovid and Henry Timrod in “Ain’t Talkin’”; rather channeling ideas and creating reconstructed worlds into his own new world: the singer of “Crossing the Rubicon” could be Julius Caesar on that day that went down in infamy as the Roman general destroyed the republic, as he “looked to the east and crossed the Rubicon”. That is the direction Caesar would have crossed the river that goes gently as she flows north into the Adriatic. But you won’t find the line in Suetonius’s Life of Julius Caesar, or in Caesar’s own history of the Civil War. Along with the classical world the song tells us the “Rubicon is the (not “a”) Red River”, taking us back through Dylan’s 1997 song “Red River Shore”, which itself takes us to the Red River of Dylan’s native northern Minnesota and the Texan Red River Valley of the Jules Verne Allen song that Gene Autry sang in the movie of the same name. That’s just a tiny part of the intertextuality of Rough and Rowdy Ways, ancient and modern alike.

As I have already mentioned, on Modern Times, Dylan refers to a lot of verses from Ovid’s relegatio works (Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto). In “My Own Version of You”, from Rough and Rowdy Ways, he sings of the “Trojan women and children” who “are sold into slavery”, and you notice that he is not referring to Euripides’s play The Trojan Women but rather to Virgil’s Aeneid II. What is Dylan’s journey? Is he still “a stranger here in a strange land”, as he sang in 1997 in “Red River Shore”?

Who isn’t? If the past is a foreign country, just by living on in time we all remain strangers in a strange land, where nothing looks familiar. But Dylan’s creative memory allows us to go back with him and straighten it out, recreate worlds that embrace our own lived experiences—worlds that contain multitudes. Dylan’s journey is a life, or multitudinous lives, in song, and it’s been a pleasure for countless thousands of us to have sailed, and be sailing, with him on that journey.

“I’ve already outlived my life by far.” So says the singer of “Mother of Muses”, sounding like Virgil’s Sibyl, who is given long life by Apollo, but without eternal youth, which is what makes her human and like the rest of us. That’s just another way of being a stranger here in a strange land, with time and space pretty much interchangeable. That’s also just one of the ways Dylan’s always written and sung our songs for us.

Thank you very much for your time, Professor Thomas.

(Samuele Conficoni)