Share This Article

The Hamburger label 30M Records is an intercontinental phonograph. Its pivot hinge moves a funnelled horn to bring sounds of Iran out of Iran to the world. They have a tender reverence for tradition. The 30M name is a cryptic derived from a 12th century mystic poem. In the poem, 30 birds (Persian, sī murğ) flock to find their king, discovering not only that there is no king, but that their winged efforts had in fact made them kings. The label also embraces modern Iran where analogue-altered sorna flutes and kamancheh (spike fiddle) play koron (quarter tones). Having briefly explored some of their back catalogue, I am keen to return to explore more of Iran’s sounds, and the techniques employed. For example, how can I identify a dastgāh, and what melody makes a particular gusheh?

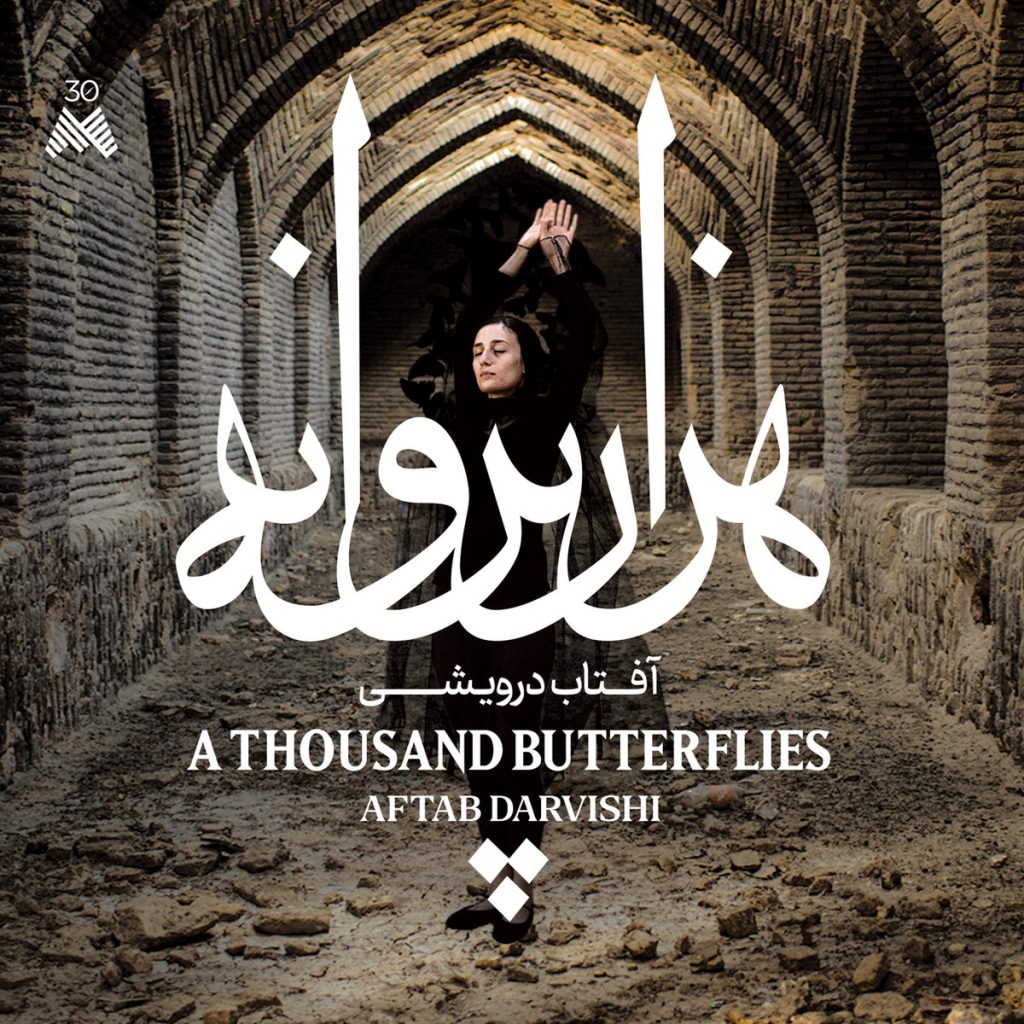

My present focus today is not on the modal system classifications that define Iranian classical music, but on Aftab Darvishi and her ‘portrait album’ titled A Thousand Butterflies. The composer has an impressive curriculum vitae. Her compositions include commissioned work for ’50 For The Future: The Kronos Learning Repertoire’ and a reimagining of Puccini’s opera Turandot titled ‘Turan Dokht’. A Thousand Butterflies marks more than a decade of her writing. The album opens with longbowing on ‘Sahar’, which Darvishi describes as the dawn chorus of Kermanshah, an ancient city in western Iran. When I listen to this, I envisage an orange-brimmed skysill contrasting the deep cerulean and royal blues of the Tekiye Moaven Al Molk. I see night lifting from the trees in the Taq Bostan. The cellos wind-dance and build and hearten until everything is suddenly revealed in luminous glory: the sun has strewn her rays across this lasting land. The tone changes on ‘Hidden Dream’, the only live track on the album. The soft reeds of a quartet of saxophones build upon the feeling of newness that ‘Sahar’ imbued. The soothing vibrato permeates warmth. The piece ends with murmurings that descend into quietude, then silence.

Narration is important in Darvishi’s work. The title track of this album has been written to include three movements, each one representing immigration. The movements are not discrete but share the same instrumentation: piano and clarinet. There is a feeling of bewilderment on the first movement. It feels ruminant. There are few stops, and as such, there is little air. The piano is heavy. Its bass notes are occasionally echoed higher in the octave. The clarinet and piano slowly peeter away as if gazing together into a new distance. The clarinet is lighter in the second movement. There is longing here, possibly for home that is no longer home. The sound is delicate. In contrast to the airtightness of the first movement, Darvishi provides space for the listener to breathe. The clarinet plays a gentle melody throughout and acts as an anchor (this represents hope to me). The third movement is brighter. The pianist uses a broader range of the scale. The clarinet flutters and changes rhythm. At points it almost cries out in reedy catharsis. The piece has now become butterfly-like. Its wings are the transparency of sound. It is sky-bound.

On her website Darvishi describes the album as evoking “a life that has crossed continents”. This is reflected in the distinctiveness of each piece. An interesting observation is the sequential lengthening of each track. ‘Sahar’ clocks in at just over six minutes and ‘Plutone’ concludes at nearly fifteen minutes. I think the lengthening of each track immerses the listener deeper in Darvishi’s aural landscapes, the most complex of which is ‘Forgetfulness’. This is almost entirely devoid of narrative and opens with a musical oxymoron of tremolo and legato, where trepidation is met with calmness. The strings are played sul ponticello (high near the bridge). They are hoarse. The reeds are hushed. The stringed instrumentalists and flautists dance around atonality and lyricalism. I think I can hear augmented seconds and chromaticism, typical of Iranian classical music. I have read that the music of Iran typically makes little use of harmony with solo performances having a position of prominence. There are elements of this on ‘Forgetfulness’ (the strings take the lead at points). This is also evident on the album’s title track where the clarinet stars.

In musical composition, the true skill is the appreciation of balance and an understanding that individual parts construct the whole. I cannot think of a better example of Darvishi’s mastering of these principles than in her final piece, ‘Plutone’. I have listened to this countless times. Its name immediately conjures thoughts of the dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt. We are somewhere faraway here. The breathy reeds and droning bells kindle a cosmogonical spirit. The tones are crystallophonic. They are glassy and enduring. They morph to become dial-like, as if they are trying to communicate with one another. The violas and cellos lift us from the blackness of these droning inklings. They strings open but stop short of an adagio. The bells continue to build and shape to become something altogether greater, reaching out for higher frequencies. A quiet piano motif is played in fifths. The bass clef rumbles. The piece eventually becomes a giant orb that is filled with resonating eddies and beautifully balanced instruments that crest and fall together. ‘Plutone’ is quite simply a masterpiece in ambient electronica. I think its success lies in its measure. Measure in time, and tone. Measure in each of its movements. Darvishi maximises the synergy of her instruments so that they ripple to become swells and torrents that wrest emotions from the listener. I can tell you that this piece has drawn me inside out and laid me bare.

(ANDREW C. KIDD)

The Monolith Cocktail è un blog indipendente con base a Glasgow, Scotland (UK).

Le ragioni della collaborazione tra Kalporz e The Monolith Cocktail puoi leggerle qui.