Share This Article

With a name woven into the very fabric and soil of Mali, no one performer can claim to represent such a multifaceted culture and land quite like the venerated Ali Farka Touré. That rightly celebrated titan was able to channel the various traditions of a people as diverse as the Songhaï – the ancestors of a predominantly Muslim community that once dominated the Western Sahara in the 15th and 16th centuries – and the Bozo fishing communities of the Niger River. In between that, absorbed into his burgeoning craft, Ali’s many job roles – from subsistence farming on the family land to mechanic, taxi driver and ambulance driver – brought him into contact with the pastoralist Fula and endeared him to the wonderful pentatonic harp and female voiced music of the Wassoulou region – an historical and cultural area without defined borders that on a modern map amorphously spreads out into Mali, the Ivory Coast and Guinea.

Many of which, especially the Wassoulou sound, can rightly lay claim to giving birth to our Westernised form of blues music. But don’t ever dare utter its name, as Ali, when later exposed to and picked up by audiences in Europe and the States, was saddled with that “blues” tag. He would famously dismiss such comparisons, favouring the term “local” music instead. It’s an important distinction in understanding his music. With no real equivalence in the West, the music press and media were still quick to label it so. It must be said that after first encountering a six-string acoustic guitar after seeing a 1956 ballet performance in Guinea, Ali would be inspired to tune into the radio waves emanating from across the ocean, especially the burgeoning blues sounds of Albert King and John Lee Hooker – the artist who, if any, can be said to have come closest to Ali’s sound. But soul and R&B also played their parts, with a liking for James Brown and Otis Redding. What Ali played was authentic music, the roots of which were taken with the enslaved unfortunate souls across the Atlantic.

Born himself in the central Mali town of Niafunké, close to the region of Timbuktu and the lifeline of the River Niger, Ali’s initial one-string apprenticeship flowered into a sound few have equaled since. As ever a deft, skilled expressive storyteller on the six-string as he was on the traditional thumbed and nimbly picked instruments of his homeland, the rural star’s fortunes and access to the music industry changed when he took on a job as a recording engineer for Radio Mali in the 1970s. He would record a septet of influential albums during that period for the Paris label Son Afric. Enter the label behind this, and previous, Ali Farka Touré showcases, the 80s formed World Circuit, whose instigator Anne Hunt made a journey to Mali to find Ali – now semi-retired – in the hope of signing him up. Hunt was successful in facilitating the concerts in London that would lead, in part, to a rush of adulation and several world tours. As the momentum grew giddy, with an abundance of Western artists lining up to collaborate, Ali recorded a run of impressive influential albums with such notable icons as Ry Cooder – they would team up for the World Circuit released Grammy Award (one of many) winning Talking Timbuktu LP. But despite the creative successes something didn’t feel right spiritually, the pull of his homeland just too deep. And so, Ali would return home to his birthplace, but maintain a recording schedule with the release of both the village inspired Niafunké and the Savane (released posthumously) albums. His collaborations would continue too, with an impressive doublet of Grammy winners with the kora maestro Toumani Diabate.

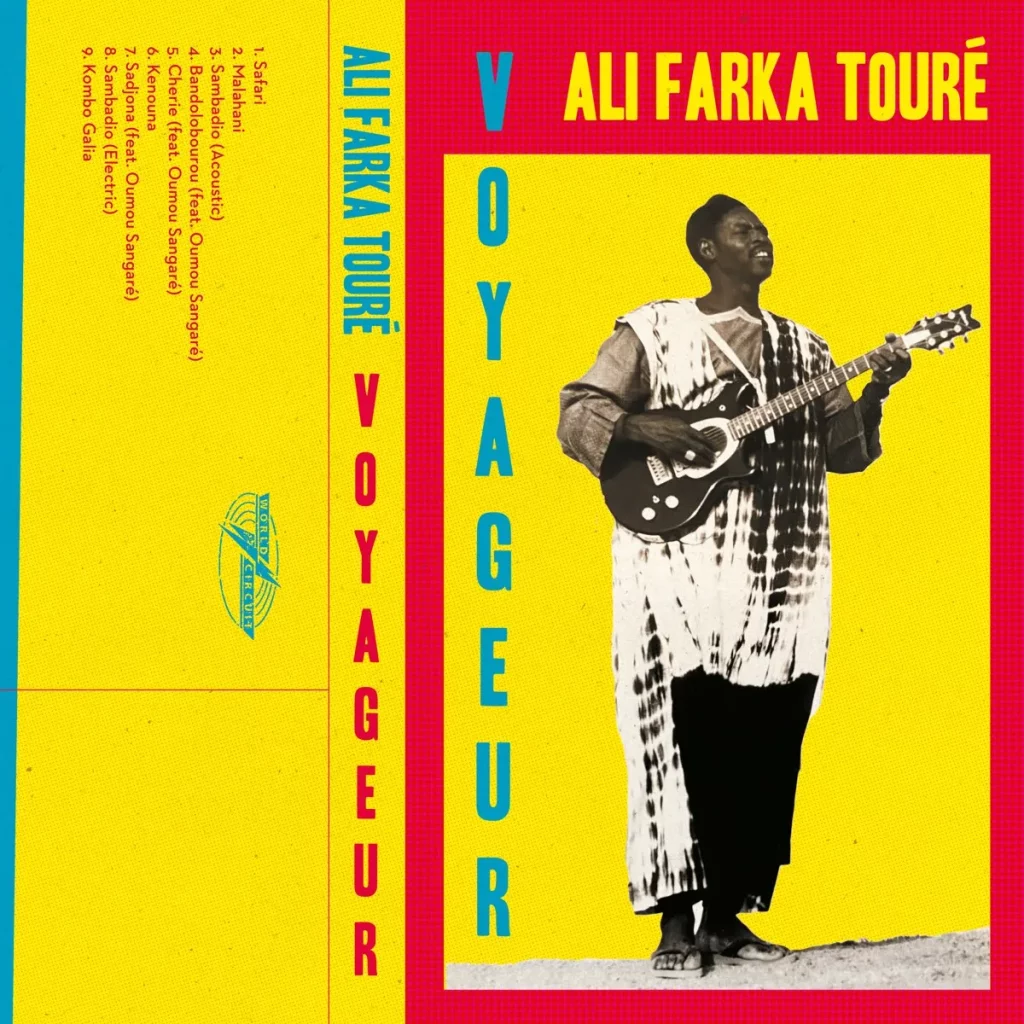

This latest project, produced by the label’s Nick Gold who spent time with the late Ali (his brilliant accompanying notes are full of vivid anecdotes and adventures spent with the Mali icon) and his scion, the equally gifted virtuoso Vieux Farka Touré (who I’m lucky enough to have seen live, and not blowing one’s own trumpet, has one of my lines, soundbites, used in his Wikipedia entry), is the first album of ‘unheard’ material from the legend since his 2010 posthumously released partnership with Diabate – released four years after his death from cancer in 2006. Voyageur is a welcoming addition to the catalogue, an incredible nomadic traverse of songs that capture Mali’s diversity and rich musical heritage; especially with his celebrated guests opening the sound up, travelling even further afield to those bordering regions that meet Mali.

Ali’s earthy timbre and twined, trilled, and constantly turning over guitar parts find a congruous union with the ngoni plucks of his guests Bassekou Kouyate (another leading light of the Mali scene) and Mama Sissoko, the R&B and soulful sax melodies and phrases of one-time James Brown sideman Pee Wee Elis and the majestic, carrying vocals of ‘The songbird of Wassoulou’ Oumou Sangaré.

Coalesced from a trio of recording opportunities (a 1995 session at Elephant Studios in London, a ‘91 session at Berry Street Studios, also in London, and captured recordings from the Hotel Mande in the Mali capital of Bamako in 2004) over a fifteen year span, the nine songs on this collection show a relaxed performer; the spiritual doyen of that often-used “desert blues” appellation almost effortlessly switching from flange fanning electric to spindled and rustic acoustic as he plucks out expressive paeans and yearns. Comparable acoustic and electric versions of the earnest Fula praised ode to ‘Sambadio’, the legendary fearless farmer, cultivator of the land, prove shining examples of this switch. The stripped-back campfire version heads down the rural, mosey route with a country hushed hoof-like rhythm, tool tilling sounds and a roots-based feel of Malian blues – even if we’re not supposed to use that term. Its electrifying companion is a merger of reedy tooted, pined, soulful highlife, Marvin Gaye and picked out guitar fanning.

But the album opens by administering the right kind of medicine with the Songhaï driven, stick rattling and fluty (courtesy of the Niger Fula flute player Yacouba Moumouni) swirls and undulations of the forthright vocalized ‘Safari’. The ‘medicine’ is this case refers to the guidance in bringing someone back to their senses. Ali sings that he has the medicine to cure ‘baliky lalo’ – “old men whose behavior is contrary to our customs and morals.” The song reminded me in part of fellow Malian guitar star Samba Touré. Later, and in a similar vein, the song of praise to the Bozo fishing elite who’ve mastered the water spirits, ‘Kombo Galia’, amps up that fuzzed electrified buzz with a sound that could be said to evoke swamp boogie and John Lee Hooker.

This album really comes alive with the addition of the beautifully, effortlessly commanding vocals of Oumou Sangaré. A World Circuit signing, friend to the late Ali, her ease permeates the lion-taming Fula Celebration to the Diona chief Amiri Amadou Dicko, ‘Bandolobourou’, and the acoustic, lifting and snozzled account of the Donso hunters, ‘Sadjona’. However, released in the run-up to this album, aired on YouTube last month, her lilted but resonating turn on the delicately spun and fluttered ‘Cherie’ duet (of a kind) is a particular highlight: a constantly nimble-fingered, light yet deeply felt laidback joy.

Ali Farka Touré aficionados will find this a welcome addition to the chronology, with recordings that many will have either never known about or been anticipating. But I’m sure there’s going to be surprises for even the most committed of fans. And for newcomers to Ali’s legacy, this album will prove a great entry point with its diversity and range, showing Ali with various collaborators and paying homage to several cultural styles, traditions. These songs are anything but unfinished scraps, demos, or downtime experiments. Instead, Voyageur is a collection of real quality.

(Dominic Valvona)

The Monolith Cocktail è un blog indipendente con base a Glasgow, Scotland (UK).

Le ragioni della collaborazione tra Kalporz e The Monolith Cocktail puoi leggerle qui